Imagine you want to train a large language model to get really good at solving tough problems—things like math puzzles or writing correct code. Usually, the way people do this is by giving the model lots of practice questions written by humans. These are called human-curated tasks: real people come up with the problems and answers, like “Write a program to reverse a string” or “What’s the derivative of x²?”. The model practices on these problem-solution pairs, and then reinforcement learning (RL) or reinforcement learning with verifiable rewards (RLVR) can be used to improve how it reasons.

But as models get bigger and smarter, collecting enough high-quality problems from humans becomes expensive, slow, and limiting. If the model might one day surpass most humans, why should humans be the bottleneck?

That’s where this paper’s idea, called Absolute Zero, comes in. Instead of relying on people to write problems, the model creates its own. One part of the model plays the “teacher,” proposing new tasks, and another part plays the “student,” trying to solve them. Because the environment is code, the answers can be automatically checked just by running the program—so no human needs to grade them.

The model learns three kinds of reasoning:

- Deduction: given a program and input, figure out the output.

- Abduction: given a program and an output, figure out the input.

- Induction: given some examples, figure out the program that works in general.

The system rewards the student for solving problems correctly, and the teacher for coming up with problems that are just the right difficulty—not too easy, not impossible.

The result is that training only on these self-made coding tasks made the model better at math. On standard benchmarks, it matched or even beat other models that were trained with large sets of human-written problems. Bigger models improved even more, and “coder” models (already good at programming) saw the biggest gains. The model even started showing “scratch-pad” style reasoning on its own, writing little notes or plans before coding—without being told to.

In short, the key insight is this: you don’t necessarily need humans to write all the practice problems anymore. If you have a way to automatically check answers, a model can bootstrap itself, creating and solving its own challenges, and still learn to reason across domains.

The authors do warn that there are challenges—like making sure tasks stay diverse, keeping the system safe, and managing the heavy compute costs—but the big takeaway is that self-play with verifiable rewards could be a new path to building smarter, more independent reasoning systems.

There’s no “exam” in the usual sense for the students – the system builds a feedback loop between the teacher (proposer) and the student (solver).

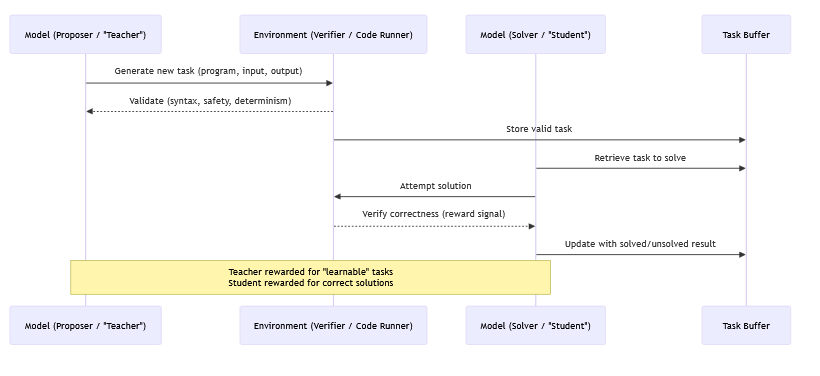

Here’s how it works step by step:

1. Teacher proposes a task

The proposer (teacher model) generates a new program + input/output pair (a problem).

Example: “Write a function that finds prime numbers up to N.”

2. Environment checks validity

The environment (code runner) ensures the task is valid: it runs, is safe, deterministic, etc.

If valid, it gets stored in a task buffer.

3. Student attempts the task

The solver (student model) pulls the task and tries to solve it.

The environment executes the student’s answer and checks correctness.

4. Rewards reflect difficulty

If the student always solves a task → it’s too easy → proposer gets low reward.

If the student never solves a task → it’s too hard → proposer also gets low reward.

If the student solves it sometimes → it’s “learnable” → proposer gets high reward.

So the proposer doesn’t “know” in advance how good the student is. Instead, it learns over time:

Tasks that end up being useful for training (medium difficulty) get reinforced.

Tasks that are too trivial or impossible fade out because they bring no proposer reward.

The proposer is like a coach who experiments with new drills, and the student’s performance on them acts as the exam. Over time, the teacher learns what kinds of problems best stretch the student without breaking them.